Slovenia On My Mind

To anyone born during the Cold War, the crossing seemed like a secret door between worlds. The train stops at the border. The passengers must step off. The sleepy station features low yellow stucco buildings with red tile roofs – something I learn later is a legacy of the Austro-Hungarian empire. As soon as I cross from the Austrian station through customs to the Slovenian one, the kaleidoscope shifts, the geometric patterns lose a bit of their parallel nature and we’re in a non-euclidean universe. The window boxes bursting with red geraniums take on a libidinous note after the gray byways of Austria. A kind of frowsy time machine sets me in a first class coach from another era. The upholstery on the Slovenian train is in faded grays and violet, the seating is velvet, and there are tiny sconces between the heavily curtained windows featuring cut class vases, long empty of flowers. I feel like I’ve stepped on the set of Hitchcock’sThe Lady Vanishes.

The railway architecture gives way to the distinctly Balkan homes of poured concrete, large and blocky with bits of rebar sticking up where another floor may go. And then through Maribor, to Ljubljana. It was 1993. I was met at the station by a young woman who was the director of Radio Študent, one of the sponsors of my visit, built around a screening of tapes from Paper Tiger Television, the video group I was part of at the time.

Ljubljana Station

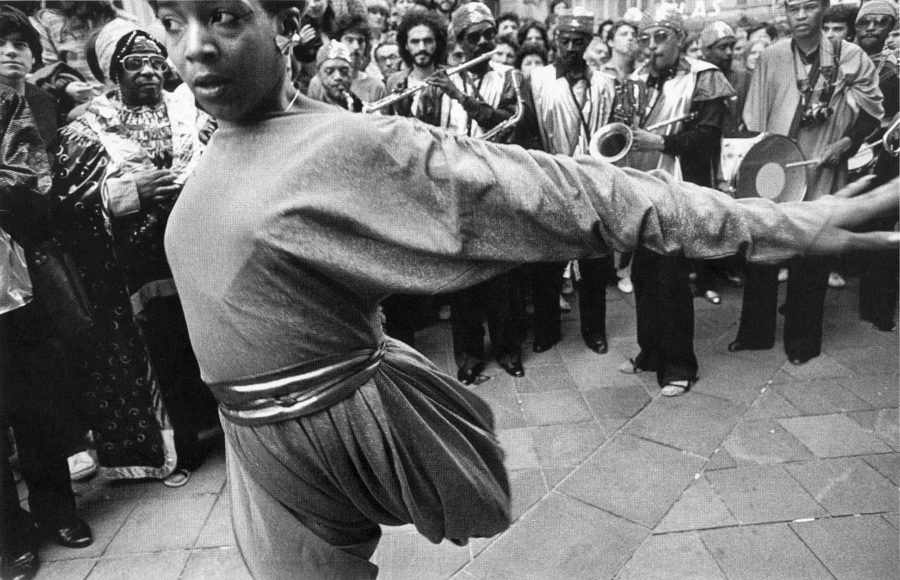

Although Slovenia has a long history as part of various empires, from the Roman to the Austro-Hungarian it is now a small nation of some two million, one that has often been on the border between peoples and empires. Ljubljana is not a large city, and my first tour did not take long. The Three Bridges. A lovely town square. The Museum of Art. And we wound up in a beer hall with a medieval cast. Thick walls, benches, a stone floor. And by himself at one of the tables, a guy in a tee shirt and jeans. I am introduced to Slovenia’s leading philosopher, Slavoj Žižek. We talked about the usual stuff, art, politics, the activist media I had come to screen. Then to Radio Študent’s studios, where I heard the history of this station which had started as part of the anti-Fascist underground resistance in WW2. The last stop on my tour of Ljubljana was a building that had a former life as a Benedictine Monastery. It was from here, I was told, that “Space is the Place” afro-futurist musician Sun Ra and his Arkestra had set out in an unauthorized jazz procession that spelled the beginning of the end for Tito’s rule in Slovenia.

Sun Ra and Arkestra, Ljubljana 1982. Courtesy of Radio Študent

The screening was a big success. I remember being teased about the Marxist analysis of the American media offered in our tapes. What could America offer to socialist thought?

For me this Slovenia was a kind of funky paradise — a conceptual art piece, Neue Slovenische style, with music by Laibach, the mock-fascist industrial group, and acerbic asides from the art collective IRWIN. A country full of young artists and intellectuals who kept themselves free from the crushing weight of ideologies of East and West. It was a space that was important in my own mind during the rise of what is now called neo-liberalism, the idea of a small culture making art and politics in an independent and fair-minded vein with a strong dose of humor.

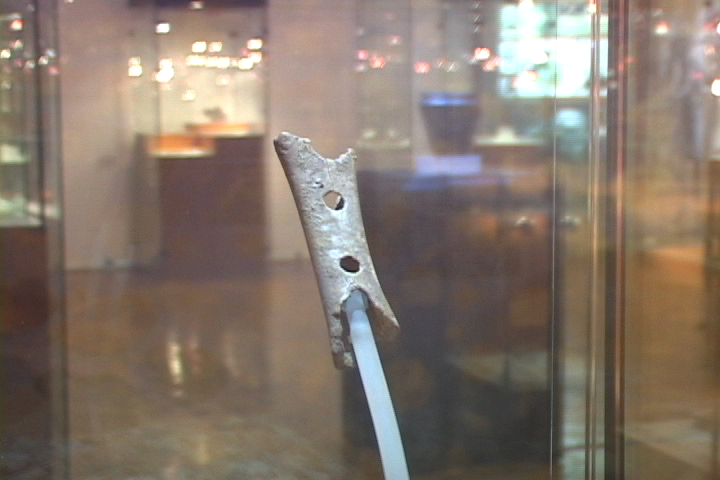

It was years before I went back, this time to a country suffering seriously from the 2008 crash, and on a train from Zagreb where I had a chance to meet artists from across the Balkans with the WHW curatorial collective at Galerija Nova. Now I had come to film the famous Neanderthal flute, famous in Ljubliana at least, at the Museum of Natural History. The museum itself was still a monument to 19c science, a brass plaque with Emperor Franz Josef’s profile in the lobby. Tall windows and dark corridors full of vitrines and obscure specimens collected in the abundant geography of this nation small, but redolent of history.

Divje Baba Flute

The last Ice Age had covered Europe with glaciers that ended exactly in these alps, making Slovenia and Croatia’s mountain caves the home to the Neanderthal. Here the flute suggested that this maligned hominid made music and buried their dead with ceremony, belying the myth of their caveman rep. The museum’s lead scientist explained the importance of the discovery in terms of the new light it shed on the Neanderthal, and how the discovery in a cave in the Slovenian Alps was totally dismissed by American scholars.

A third visit during a summer vacation in 2014, the crash long over, The stay was pricey, the restaurants charming, the tourists clogging the riverfront and lining up for a tram to the mountaintop castle. Globalization had set in. Slovenia had rebranded itself as a cute tourist site living on Airbnb and Trip Advisor, the price of deterritorialization and proximity to the Dalmatian Coast.

There is one other image of Slovenia, not from my own experience, but from the film work of Želimir Žilnik, a Brechtian moment in one of his films, Fortress Europe, a lightly done fiction about a Russian family trying to get to Italy. Two border guards, a man and a woman, show how to sneak across into the EU. It is perhaps these last two images that are the most useful for forming a picture of Slovenia today.

“Fortress Europe” (Zelimir Zilnik, 2000)

http://www.zilnikzelimir.net/fortress-europe

As part of Tito’s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Slovenia had been a star, the lead example of the “Self-managed socialism” that was the invention of native son Edvard Kardelj. Slovenia was the first formerly communist country to join the Eurozone after the breakup. The breakup of Yugoslavia was accompanied with a rhetoric where nationalism turned to ferocious racism and famously occasioned vast atrocity. Slovenia adroitly avoided most of the terrifying fallout since it declared independence in 1990. But life as a small independent country has not been easy, and it would be impossible for an outsider to catalog the complex ups and downs of democracy here.

In June, Slovenia had elections. The top vote getter supported by Hungary’s Orban, has the populist anti-immigrant stance of governments popping up across Europe. It was that election that prompted me to think of the image of Slovenia that I somehow wanted to keep in my mind.

When I first went to Slovenia, I stayed in an apartment in a public housing block. The park nearby featured a statue of Edvard Kardelj, Tito’s right hand man, and the inventor of Self-managed socialism. Accused by Stalin of being on the border of Trotskyism or council-communism, this much lauded but hard to characterize system seemed mainly to serve to keep Yugoslavia out of the control of the Soviet economic zone, allowing for loans from the West and Yugoslavian guest workers in Western Europe. Maybe it was just the political expression of a kind of impossible independence. Although it is worth remembering that the Yugoslavian resistance to the Nazis was very real, and very different from the response of many European nations to the occupation.

From being at the forefront of workers self managed socialism to a poster child for European social democratic capitalism, to drifting slowly toward authoritarianism what happened? The signs were there. [footnote: An intriguing history of the magazine Praxis, a home for the post-Stalinist left that fell apart when the collapse of former Yugoslavia lead to the rise of Serbian and Croatian nationalism was recently reprinted by The Jacobin.] The “Non-aligned Movement” (Nassar, Tito, Nehru and Nkrumah) allowed Yugoslavia wiggle room as part of what was in many ways a third world movement. Was that image of a third way always a bit of an illusion? No doubt. But just as an escape from binaries, it felt important.

The recent elections gave former Prime Minister Janez Jansa and his right-wing Slovenian Democratic Party the largest number of seats. Parliament meets today, on June 22nd. And the other parties have vowed not to form a coalition with Janša. Janša is a fan of Hungary’s Orban, and it was noted that one Hungarian media mogul linked to Orban took control of a couple of media outlets in Slovenia. The authoritarianism and anti-immigrant populism that has spread across the globe is getting its day in Slovenia.

Slovenian Democratic Party Poster, 2018.

See:http://www.pengovsky.com/2018/05/30/2018-parliamentary-election-bells-and-dog-whistles/

Is this was still the same country where a jazz procession from a former Benedictine monastery could start a revolution? The original procession was in 1982. One can only hope Sun Ra would be allowed in today.

Marty Lucas

Footnote: Radio Študent, Ljubljana is still alive and well: https://radiostudent.si

And you can view a 32nd Sun Ra Anniversary Memorial Procession in 2014: